Use of Cookies

Our website uses cookies to facilitate and improve your online experience.

Tenzo Kyokun was compiled by Dogen Zenji when he was thirty-eight and was living at Koshoji in Uji. This is a book of instruction for the “Tenzo”, who is the monk in charge of preparing meals in a Zen temple.

When Dogen Zenji was twenty-four years of age, he crossed over to Song China in the company of another monk, Myozen, in order to search out the true Buddhist teachings.

Dogen wrote, “The name of Buddhism has been heard in Japan for many long years now, but as for correctly preparing food for those undergoing training in the Monks’ Hall, it has never been written about, nor has anyone ever taught me about it.”

Just as he writes in Tenzo Kyokun, Dogen Zenji went to Song China, and from his meeting with different kinds of people came to realize that the work of a Tenzo is not that different from the practice of zazen.

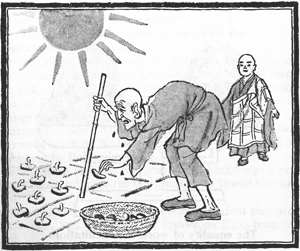

The following is an experience Dogen Zenji had while staying at Keitokuji temple in Chekiang Province in China. On the way to visit his traveling companion, Myozen, who was recuperating from an illness in the infirmary, Dogen Zenji passed the Buddha Hall. There he saw an old monk whose back was bent like a bow and whose eyebrows were as white as the feathers of a crane. The old monk was drying mushrooms one by one on the tiles which paved the courtyard.

In a large temple great quantities of mushrooms are consumed, therefore, many are dried in the hottest part of the summer and put away for future use. The old monk, Yung Osho, supported himself with a bamboo staff, and in spite of the heat wore no hat, so he was drenched with sweat. He was totally absorbed in his task. In the scorching sun the paving tiles were as hot as an oven.

This sort of duty on such a day would not have been easy even for a young person, and for an old monk nearing seventy it must have been especially trying.

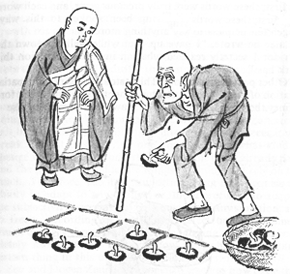

The young monk, Dogen, seeing this, felt pity and walking up to the old man asked, “How old are you?”

Yung Tenzo stayed his busy hand long enough to answer, “This year I'll be sixty-eight.”

“A person of your age shouldn’t be doing this kind of work; why don’t you get someone else to do it?” Dogen suggested with concern.

“Other people are not me,” Yung Tenzo replied sharply. Dogen must have felt as though he had been stabbed in the chest.

“Yes, that’s true, but why don’t you just rest for a while? You shouldn’t overtax your body,” caringly objected Dogen.

Yung Tenzo firmly responded, “And just what other time should I wait for?” and kept on at his task.

This second arrow went into Dogen even more deeply than the first; these words were truly precious gems, and each word resounded within him. Having been spoken to this way, Dogen felt helpless to say anything more.

Later he wrote, “I gave up. But while walking down the corridor I secretly realized what an important function this work has.”

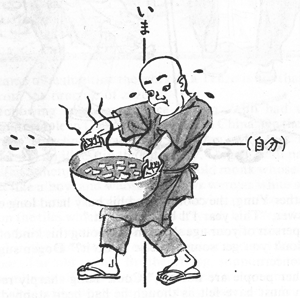

“Other people are not me.” This statement defines the spatial location of “here.” “And just what other time should I wait for” defines the temporal position of “now.” Not somebody else – me (here); not later – now. Reality is the place where this “here” and this “now”’ cross.

There has never been an age in which the ups and downs of life have been so violent as those of today.

If this expression seems trite, let me revise it and say that there has never been a period of social change and development as extreme as that of today.